By Festus Adedayo

While growing up, I went on hunting expeditions with elderly men. From there, I found out that the forest, as an ecosystem, is diametrically opposed to the human world. In the forest, the hunter exists with “other beings”- animals of different shades and character, plants – whose existences bear similarity with man’s. One of such beings is an unseen spirit whose existence the hunter can take for granted only at his own peril. In the forest, the hunter is in a continuous struggle with these beings but is seen as an interloper. In this forest community, every member of the ecosystem contests for primacy, sometimes in a mortal and fatal manner.

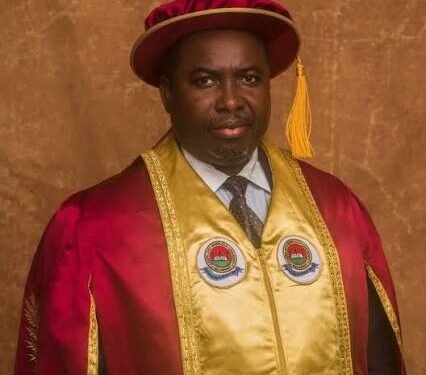

Whenever human arguments begin to sound like claptrap to me, I bail out to avoid going mad. My refuge is always among animals, in the wild. It is a place Yoruba curiously call ìgbé. Ìgbé is, literally, excreta. I find greater logic in excrement than sweet-smelling human contraptions. To explain Professor Joash Amupitan’s recent appointment as the Chairman of the Independent Nigerian Electoral Commission (INEC) and the forebodings that line the sky, I had to go in search of animals. Their lives give explanations to the weird life of man. Whether in the sullen murmur of bees, the cruel humour of monkeys, the deafening roar of lions, the ugly beauty of hyenas or the artistry in the skin of zebras, the wild is a better place to find peace of mind. Or don’t you think so?

In Ayo Adeduntan’s seminal work, What the forest told me: Yoruba hunter, culture and narrative performance (2019), the author conducted an interview with Ògúnkúnlé Òjó of Agúnrege village in Oyo State. Adeduntan narrated how Òjó’s hunter master, Ògúnòṣun, married an efòn, the buffalo. In description, the African buffalo is one of Africa’s ‘big five’ safari animals, alongside rhinoceros, elephant, leopard and lion. Living only in Africa and Asia, the buffalo is reputed for its huge horns. Though a herbivore like cows, feeding only on plants, the animal often falls prey to predators like hunters, lions, leopards, hyenas and wild dogs. It can also be vicious; in order to defend herself, the buffalo strikes its prey with her horns.

According to Ògúnkúnlé Òjó, this particular day, he and another colleague on hunting expedition had shot the buffalo in the Agúnrege village forest. The animal immediately fell. Apparently frightened by the monstrosity of their kill, one of them had to run home to fetch their master, Ògúnòṣun. As they were about to get to the spot where the animal was felled, narrated Ògúnkúnlé, they suddenly saw a very pretty woman walking towards them. I remember Odolaye Aremu, Ilorin Dadakuada music lord, comparing the suddenness of death to the instantaneous blow of a calamity. He sang, “…pèkí làá ko èèmò.” Said Ògúnkúnlé, “we ran into the animal, that is, the wife. She was a very beautiful woman” which in Yoruba is, “àfi pẹ̀kí n l’a bá pàdé ẹran l’ọ́nà, èyuùn ìyàwó. Arẹwa obinrin ni”. What Ògúnkúnlé implied was that the woman they met on the road to the buffalo’s remains was the same buffalo who had now transformed into a beautiful woman. It reminds one of Fagunwa’s Igbo Olódùmarè and how Olówóayé, swept off his feet by the sultry beauty of a woman named àjẹ́, was oblivious that he was making advances to a spirit woman.

What eventually transpired between Ògúnòṣun and the buffalo-turned-beautiful woman is instructive. “Our master exchanged greetings with her (the animal). She greeted our master, kneeling down in respect. This is no hearsay; I, Òjó the hunter, was present there that day. Our master wooed her and they both agreed to marry each other. She (however) warned: ‘Now that you have decided to marry me, be informed that the day you, out of anger, call me an animal, that day would be your last. It would not offend me as much if you hit me so much that I am wounded and bleeding.’

“So they got married. She became pregnant and had the first child, the second and the third child. There was a quarrel between her and my master one day. As they quarreled, my master angrily insulted her: : ‘Àb’órí ì rẹ burú ni, ìwọ ọmọ ẹranko yìí’ – ‘You good-for-nothing unlucky daughter of an animal.’ ‘Oh!’ the woman said, ‘You are done for.’ That was where the trouble started.”

Writes Adeduntan, “The woman is at once seized by a paroxysm of anger in which she is transformed into a buffalo, bristling with vengeance. The hunter, now helpless and a fugitive, runs towards Ìgbàdì, a prehistoric mountain on the outskirts of the village, where the buffalo catches up with him. The buffalo gores him badly before fleeing into the forest, never to return. The hunter survives the attack, but limps from the resulting fracture in his leg until his death.”

Ògúnkúnlé Òjó then ended the story, stating that the buffalo woman then turned into her pre-marital animal state. “Yes. It is no hearsay. She transformed into an animal by Ademọla’s father’s house beside Igbadi Hill. That was when the two of them started to fight. Our master tried all his power and failed. That was how the woman ran away forever. One of the children is dead. The remaining two are still in my master’s house,” Ògúnkúnlé said.

The forest is a realm that is implicitly uncertain. Those who claim that forest conversations between the hunter and other beings who live in the wild are purely African fantasy underrate our reality. The truth is that the hunter shares the forest cosmos with other beings. While the hunter believes he possesses some superiority over animals and other beings in the forest, the truth is that it is a shared world. Indeed, the Yoruba worldview does not approve of man’s superordinate status claim in relation to other earthly creations. He is thus in constant war against these forest antagonists whom he cannot pacify and who also see him as a usurper. This reminds me of a childhood fairy tale we were told about Segbe, a boy who veered into the wild on a festival day to hunt game. The animals descended on him and made a barbecue of his flesh. When the search party scoured the forest for him the second day, the birds sang “Who is there searching for Segbe? Human beings were celebrating in their homes. We, animals, were having ours in the forest. We have made a meal of Segbe’s flesh.”

In animals, there is no hypocrisy, no pretension. Victims and victimizers are aware of their naturally ordained roles and do not pull any shroud over this. In their wild habitat, these mammal forebears of man seem to explain better the contradictions of human life and the ill logic of the life of man. It prompted my disagreement with Fela Anikulapo’s concept of “animal talk”. While excoriating the Muhammadu Buhari military government’s War Against Indiscipline philosophy of openly beating offending Nigerians, Fela called that philosophy a talk of animals. My disagreement is that, animals’ lives speak to man but man is too deaf to listen.

In Yoruba hunters’ narratives, while there is always a hunter, animal and spirit relationship, this symbiosis often ends up in calamity. While D. O. Fagunwa’s narrative of the relationship between the trio of man, animal and spirits in the wild was fabulism, he took it out of the real life man-animal forest ecosystem relations and encounters. Fagunwa’s books opened our eyes to the symbiosis of this relationship. You can see this relationship in the encounter between Olówóayé, Fagunwa’s hunter and protagonist, and the one-eyed elf called Èsù-kékeré-òde, in the book he entitled, The Forest of God, Igbó Olódùmarè. In another of his book, Ogbójú ọdẹ Nínú Igbó Irúnmalè, this contest for supremacy between man and the spirit was illustrated by how a character called Tèmbèlẹ̀kun, a flesh-eating spirit, devoured Lamọrin, a hunter. Such is the nature of the dog-eat-dog relationship in the wild. ̣

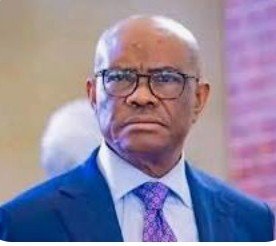

So, last Thursday, as Professor Amupitan appeared in the Nigerian senate for screening, he suddenly pounced on my mind like a rampaging leopard. Whenever a hunter encounters an animal in the wild, his discerning mind tells him whether she is indeed an animal or an animal-turned-man. Putting on that same lens, what I saw last Thursday was an incestuous relationship between a hunter and a buffalo that would soon go awry. The hunter-buffalo’s love-turned-sour narrated above tells me I wasn’t mistaken. My reading is that of a tragic relationship that will soon come full throttle between Aso Rock, Amupitan and the Nigerian people.

History is Amupitan’s first nemesis. It holds that, like Ògúnòṣun, the hunter who got married to a buffalo-human, the new INEC boss is entering a graveyard of history where he would be so badly gored that he might emerge therefrom with a permanent scar. Since Sir Hugh Clifford’s Legislative Council election of 1920, Nigeria’s elections have been the graveyard of their electoral umpires. Though the electoral umpire’s name was not mentioned in history, after this 1920 election and the ones held from 1923-1938 which involved the House of Docemo (Dosumu) and the status of Oba of Lagos, for elections in Nigeria, there has been the proverbial case of no respite for the hen that perches on the rope and none for the rope either. There was crisis in the 1941 election that had NYM foundation member and Secretary General of the Nigerian Road Transport Union, Samuel Akisanya and Ernest Sese Ikoli, another NYM foundation member, president and editor of the NYM newspaper organ, Daily Service.

Since then, Nigeria has had electoral chiefs whose tenures ended in fiasco and, or ignominy. One was Ronald Edward Wraith who came into office in 1958. He was followed by Eyo Ita Esua (1964 – 1966). Esua, from present day Cross River State, was a teacher and unionist. Appointed in 1964 by Prime Minister Abubakar Tafawa Balewa, Esua became Nigeria’s first known indigenous electoral umpire and presided over the 1964 parliamentary and 1965 regional elections. Since then, we have had other indigenous umpires like Michael Ani, a career civil servant and former commissioner in General Ironsi’s government, who also hailed from Cross River State. Ani was appointed by the Olusegun Obasanjo military regime which created what it called the Federal Electoral Commission (FEDECO). Ani then became the umpire of the controversial 1979 elections which returned civil governance after 13 years of military rule.

In 1980, President Shehu Shagari appointed Victor Ovie-Whisky who was in that office till 1983. From 1987 when General Ibrahim Babangida appointed Eme Awa, a professor of political science as head of an election body he christened National Electoral Commission (NEC) as part of his transition to civilian rule, Awa was in NEC till 1989. He began the fad of academics being heads of Nigeria’s electoral bodies. Awa was succeeded in 1989 by Prof Humphrey Nwosu, who was there till the stillbirth election of 1993. He was succeeded by Prof Okon Edet Uya, a historian from Akwa Ibom State in 1993. Uya conducted no major election by the time General Sani Abacha took over the reins of power in November 1993. He then dissolved the NEC in 1994 and rechristened it the National Electoral Commission of Nigeria (NECON).

Abacha diluted the long obsession with academics as electoral umpires with Chief Sumner Dagogo-Jack, a lawyer and administrator from Rivers state. He conducted the local and legislative elections of that period and was in office till Abacha’s death in 1998. Gen Abdulsalami Abubakar then dissolved NECON and established the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC), putting Ephraim Akpata, a Supreme Court judge from Edo State, at the helm of affairs. Akpata conducted the 1999 general elections which produced Obasanjo as president. When he died in 2000, Obasanjo appointed an academic and technocrat, Abel Guobadia to conduct the 2003 elections. Guobadia was there till May 2005 when he was replaced by another professor, Maurice Iwu who was in office from June 2005 to April 2010. Iwu’s INEC superintended over the 2007 general elections. Then came Attahiru Jega in June 2010 and was there till June 2015, and replaced in November 2015 by Mahmood Yakubu, a Bauchi State indigene.

Enters Amupitan. His first shot in the senate last week was to confront the unpalatable graveyard image of electoral umpire bosses with beautiful semiotics. In semiotic theory, users deploy signs and symbols to create meanings. This they do through language, gestures and images. As he appeared at the senate screening exercise, the professor of law appeared with his family. As a student of semiotics, Amupitan knew that a portrayal of the presence of his children on his first interface with Nigerians has great powers. With it, people could be convinced that, as a family man, he would be humane. However, the reality of what he is about to contend with far transcends the tender-heartedness of the family.

At the senate, Amupitan spoke very well. Just like his predecessors. The professor from the sleepy town of Ayetoro Gbede said his life is influenced by a tripod of God, hard work and mentorship. He then promised to audit the system at INEC and return trust and integrity to the Nigerian electoral process. He even advocated an electoral offences commission and a whistle-blowing policy.

Soon, Amupitan will realize that he is in the same boat with persons for whom God exists only as a political slogan or refrain. Beyond their lips, there is no one so called. To his shock, he will realize that, in this God thing, he is alone. Again, more than ever before, Amupitan, the literal rendition of which means a history-maker, will indeed make history. He will also tell a story. What story he will tell and the history he will make are part of the omen of a gathering cloud in the sky I see. Vultures are already hovering, signifying that the story the professor will tell will not only not be significantly different from his predecessors’, it could be worse. First is that, unlike many previous elections, Nigerians have the painful belief that the winner of the 2027 elections, especially the presidential election, is already known. This will leave Amupitan to contend with his own ambiguities.

Second is the gale of defections that has rocked Nigerian politics in the last few months. The defections render party politics no different from the petty business of market square transactions. They thus make Amupitan’s job a potential failure. The belief is that the Senators/House of Representatives members and governors changing parties like chameleon changes colour, are driven by the quest to have the party at the federal lip-frog them into victory. How would Amupitan deny the party of his appointor victory in 2027?

Already, Amupitan’s ambivalent heritage may also sound the death knell on his electoral umpire role. While the presidency gleefully flaunted him as having “hailed from the North Central,” everyone knows that putting Ayetoro Gbede as northern Nigeria is one of those geographical mis-ascriptions of today’s Nigeria. A town in Okunland, in Kogi West Senatorial District of Kogi State, Amupitan hails from this town founded in 1927 by early Christian converts. The truth is, Ayetoro Gbede is Yorubaland. So, if northern Nigeria, which is today embroiled in a fight with the Villa on allegation of under-developing the North, loses the 2027 election to Amupitan’s perceived brother, there cannot but be wahala.

Pardon my pessimism. What I see is Amupitan, with his lustering credentials, ending up brutally bruised. This liaison with a buffalo-turned pretty woman will not likely end well.

•Published by the Sunday Tribune.